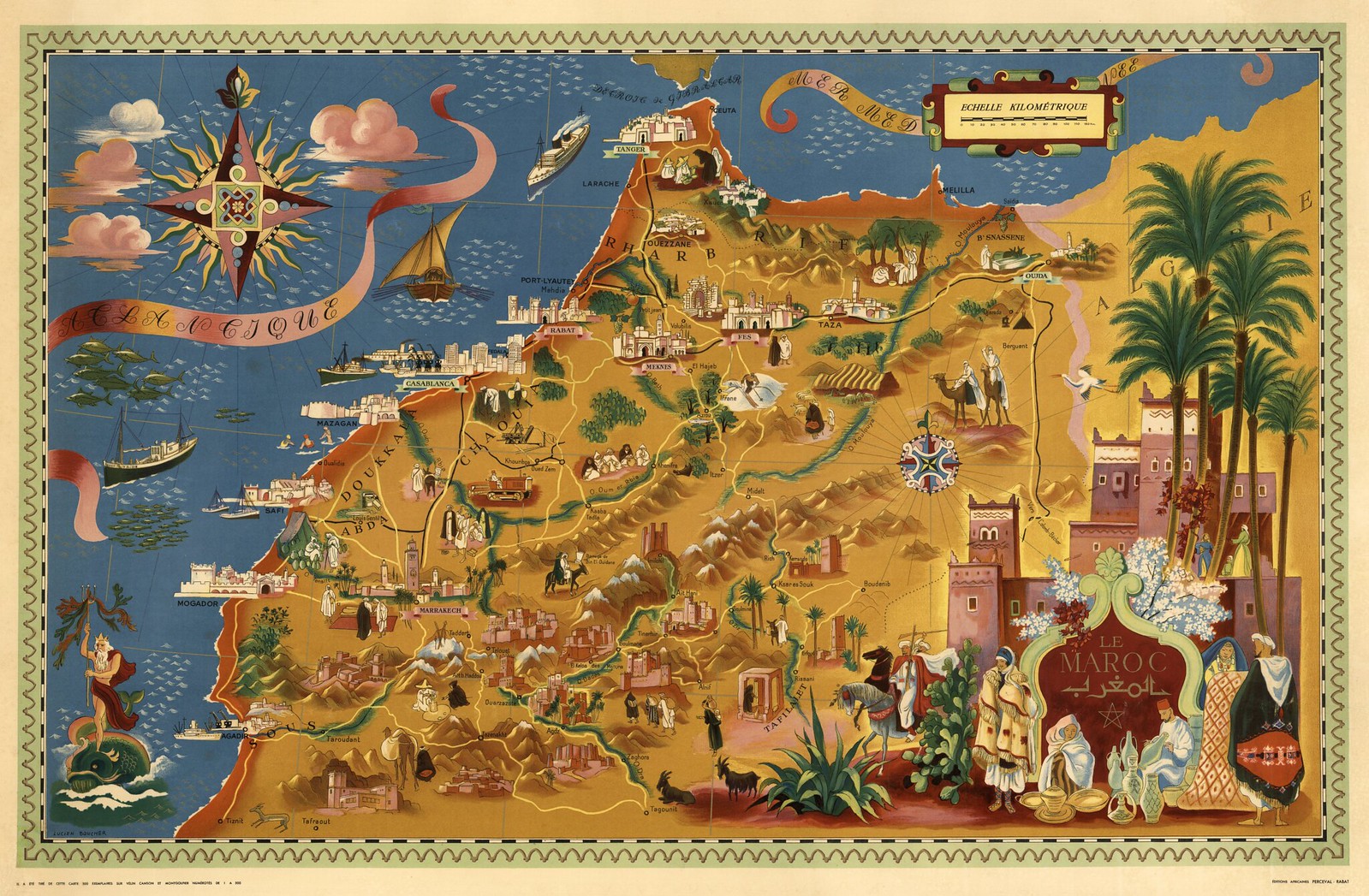

Today Tajine editor Graham Cornwell discusses a beautiful but politically fraught Air France map of colonial Morocco from the Rumsey Map Collection. Here's a full sized version of the map (127 mb) and some other Air France maps.

In 1948, France faced a looming crisis in its North African

colonies. Algeria, Morocco, and Tunisia joined colonized populations around the

world renewing their push for independence after World War II. In Morocco,

Sultan Mohammed V began to press the French, especially after he allegedly

received a tacit endorsement for Moroccan independence from Roosevelt at the

end of the war. Protests increased, and although things had not yet turned

violent, but Protectorate officials had begun arresting (and sometimes exiling)

prominent nationalist leaders.

Yet the post-war years were prime time for Morocco’s colons. C.R. Pennell calls it the

“Indian summer of settler colonialism.” The Protectorate opened up new lands to

settlement, especially to war veterans, and a massive infrastructure boom

helped make Morocco an attractive place to invest. This 1948 Air France

promotional map captures the dream of colon

Morocco at its heyday: the near-famines

of the previous decade over, indigenous unemployment finally decreasing, and a

new crop of bourgeois settlers opening up new businesses in Moroccan cities.

The map depicts the northern two-thirds of the French zone,

as well as the Spanish zone, which is designated by a dotted line just south of

the Rif Mountains but not identified as such. It’s a beautiful print, designed

to attract tourists to come see a Morocco that was still traditional but beginning

to show the hallmarks of paternalist French expertise. There’s a surprising

amount of accurate detail—one can make out the distinct, pentagonal minaret of

the Mazagan (El Jadida) kasbah mosque while the ksour towns of Agdz, Ait Ben Haddou, and Kelaa M’Gouna actually

bear a resemblance to the real things.

There are only four Europeans in the image. Three bathe off

the coast of Mogador (Essaouira), while one skis the slopes near Ifrane. Sun

and snow aren’t the only draws: in the Middle Atlas, a lone boar’s head

indicates hunting opportunities and a trout near Azrou points to good fishing.

The map’s Morocco shows no hint of nearly fifteen years of intermittent drought

and the hardships of World War II. Moroccan workers reap abundant crops while

the Atlantic teems with sardines and tuna.

There are only four Europeans in the image. Three bathe off

the coast of Mogador (Essaouira), while one skis the slopes near Ifrane. Sun

and snow aren’t the only draws: in the Middle Atlas, a lone boar’s head

indicates hunting opportunities and a trout near Azrou points to good fishing.

The map’s Morocco shows no hint of nearly fifteen years of intermittent drought

and the hardships of World War II. Moroccan workers reap abundant crops while

the Atlantic teems with sardines and tuna.

Most of the Moroccans depicted are men, and most are pictured at work, whether collecting water from a well in the Tafilalet,

riding a tractor in the Chaouia, or collecting olives in a Rif foothills grove.

Even snake-charming might have counted as a profession in French eyes. The effect is to make Moroccan labor appear like other natural resources: mines

in the hills above Berguent in the east and the phosphates region near

Khouribga in the west, orchards of the Gharb plain, vineyards of the Beni

Snassen. Here, in startling technicolor with Neptune frolicking off shore, we get the colonizer-colonized distinction reimagined as a dichotomy

between play and work.