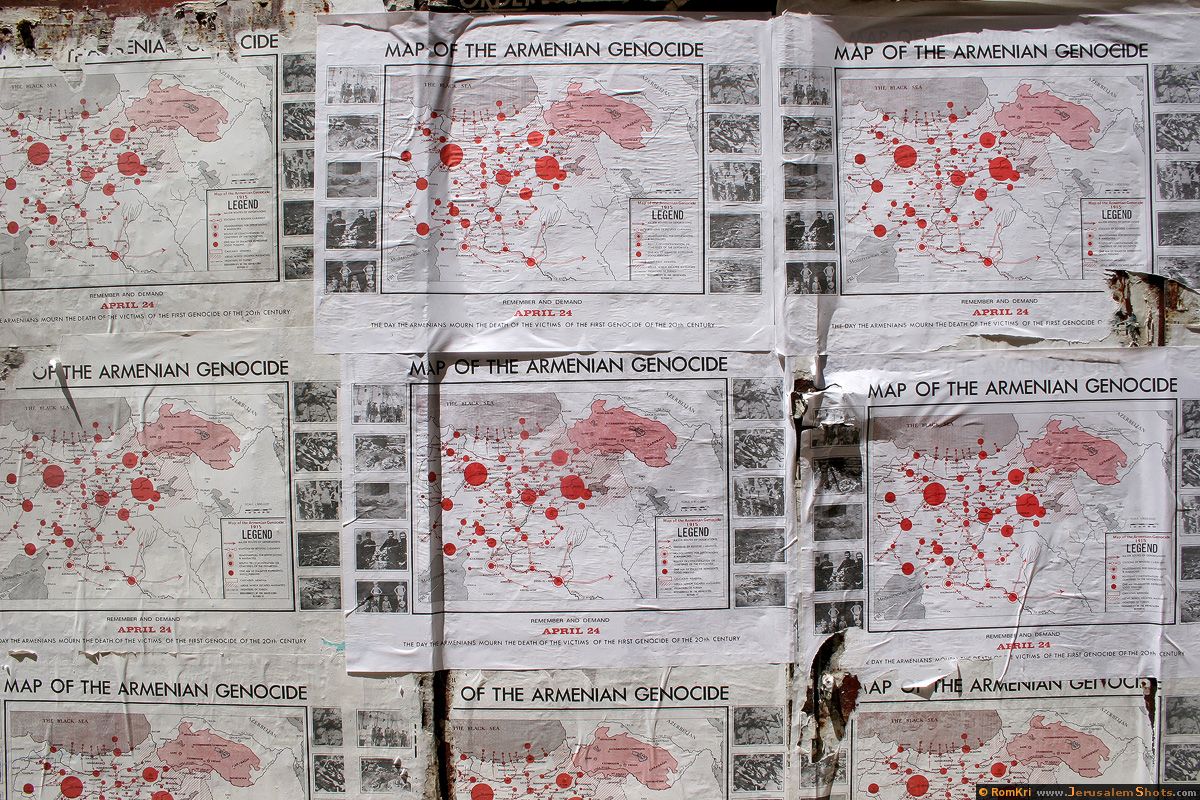

photograph from RomKri

For at least eight years now I feel like I've been trying to figure out how to articulate my views on the history and politics of the Armenian genocide. Among the many things that make it difficult is the speed at which the terms of the debate have changed. It's hard to keep track of who you're trying to argue with when people are changing their positions.

In 2007, when I first proposed a version of this week's article, I was an intern at a liberal-for-Turkey think tank in Ankara. My supervisor sort of politely explained to me that there was no way his organization could even consider publishing anything of this sort. A few weeks later they withdrew a preliminary job offer they had made me for the coming fall. When, the next year, I tried to publish the article elsewhere, friends and colleagues warned against it, citing to the Turkish government's success in making life difficult for anyone who used the g-word in print.

Trying to make a very similar argument last year, though, I was amazed that at least two thirds of the angry comments were from pro-Armenian readers. Many denounced it as an example of Turkish sponsored denialism, and suggested I was in the pay of the Turkish government. (For the record, I've gotten a number of relatively small scholarships from the Turkish government and organizations like the Institute for Turkish Studies. Let me just say that if the ANC starts giving out grants to study Ottoman Turkish, I promise to take one of those too.) On purely semantic grounds I'm not entirely sure how an article that insists on describing the events in question as a genocide can count as genocide denial, but I can understand the anger. An infuriating consequence of the Turkish government's policies over the years has been the creation of a situation where scholars either had to acknowledge Turkish suffering or the Armenian genocide. And as a result, authors like Justin McCarthy, who did serious and important work on the fate of Balkan Muslims, sank into the role of anti-Armenian hacks. The one thing no one could do was acknowledge a historical relationship between Turkish and Armenian suffering without, as the Turkish government demanded, completely equating them. Turkish denialism tainted the efforts of anyone who wanted to say there was suffering on both sides while insisting it differed greatly in motive and magnitude.

The newfound freedom with which people in Turkey can discuss the genocide will, I think, eventually resolve the polarization that has made this issue so intractable. Perhaps its because I think this debate really is about history, and not, like so much else, about politics packaged in historical language, that I actually think historians will in time be able to make real progress in resolving it. That said, it's discouraging to see that Turkey's newfound openness on the genocide is matched by a growing list of things people can't discuss there anymore. I'm not sure anyone would have predicted a situation where acknowledging the Armenian genocide felt safer than criticizing the government. Or that as old Kemalist myths were eventually discarded they would be so quickly replaced by new forms of bad history.

But against all evidence, as the world commemorates the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide this year, as we join together in demanding recognition and justice, let's try to do so with the sincere, if naive, faith that honest history is the best antidote to dishonest history.

For at least eight years now I feel like I've been trying to figure out how to articulate my views on the history and politics of the Armenian genocide. Among the many things that make it difficult is the speed at which the terms of the debate have changed. It's hard to keep track of who you're trying to argue with when people are changing their positions.

In 2007, when I first proposed a version of this week's article, I was an intern at a liberal-for-Turkey think tank in Ankara. My supervisor sort of politely explained to me that there was no way his organization could even consider publishing anything of this sort. A few weeks later they withdrew a preliminary job offer they had made me for the coming fall. When, the next year, I tried to publish the article elsewhere, friends and colleagues warned against it, citing to the Turkish government's success in making life difficult for anyone who used the g-word in print.

Trying to make a very similar argument last year, though, I was amazed that at least two thirds of the angry comments were from pro-Armenian readers. Many denounced it as an example of Turkish sponsored denialism, and suggested I was in the pay of the Turkish government. (For the record, I've gotten a number of relatively small scholarships from the Turkish government and organizations like the Institute for Turkish Studies. Let me just say that if the ANC starts giving out grants to study Ottoman Turkish, I promise to take one of those too.) On purely semantic grounds I'm not entirely sure how an article that insists on describing the events in question as a genocide can count as genocide denial, but I can understand the anger. An infuriating consequence of the Turkish government's policies over the years has been the creation of a situation where scholars either had to acknowledge Turkish suffering or the Armenian genocide. And as a result, authors like Justin McCarthy, who did serious and important work on the fate of Balkan Muslims, sank into the role of anti-Armenian hacks. The one thing no one could do was acknowledge a historical relationship between Turkish and Armenian suffering without, as the Turkish government demanded, completely equating them. Turkish denialism tainted the efforts of anyone who wanted to say there was suffering on both sides while insisting it differed greatly in motive and magnitude.

The newfound freedom with which people in Turkey can discuss the genocide will, I think, eventually resolve the polarization that has made this issue so intractable. Perhaps its because I think this debate really is about history, and not, like so much else, about politics packaged in historical language, that I actually think historians will in time be able to make real progress in resolving it. That said, it's discouraging to see that Turkey's newfound openness on the genocide is matched by a growing list of things people can't discuss there anymore. I'm not sure anyone would have predicted a situation where acknowledging the Armenian genocide felt safer than criticizing the government. Or that as old Kemalist myths were eventually discarded they would be so quickly replaced by new forms of bad history.

But against all evidence, as the world commemorates the 100th anniversary of the Armenian Genocide this year, as we join together in demanding recognition and justice, let's try to do so with the sincere, if naive, faith that honest history is the best antidote to dishonest history.