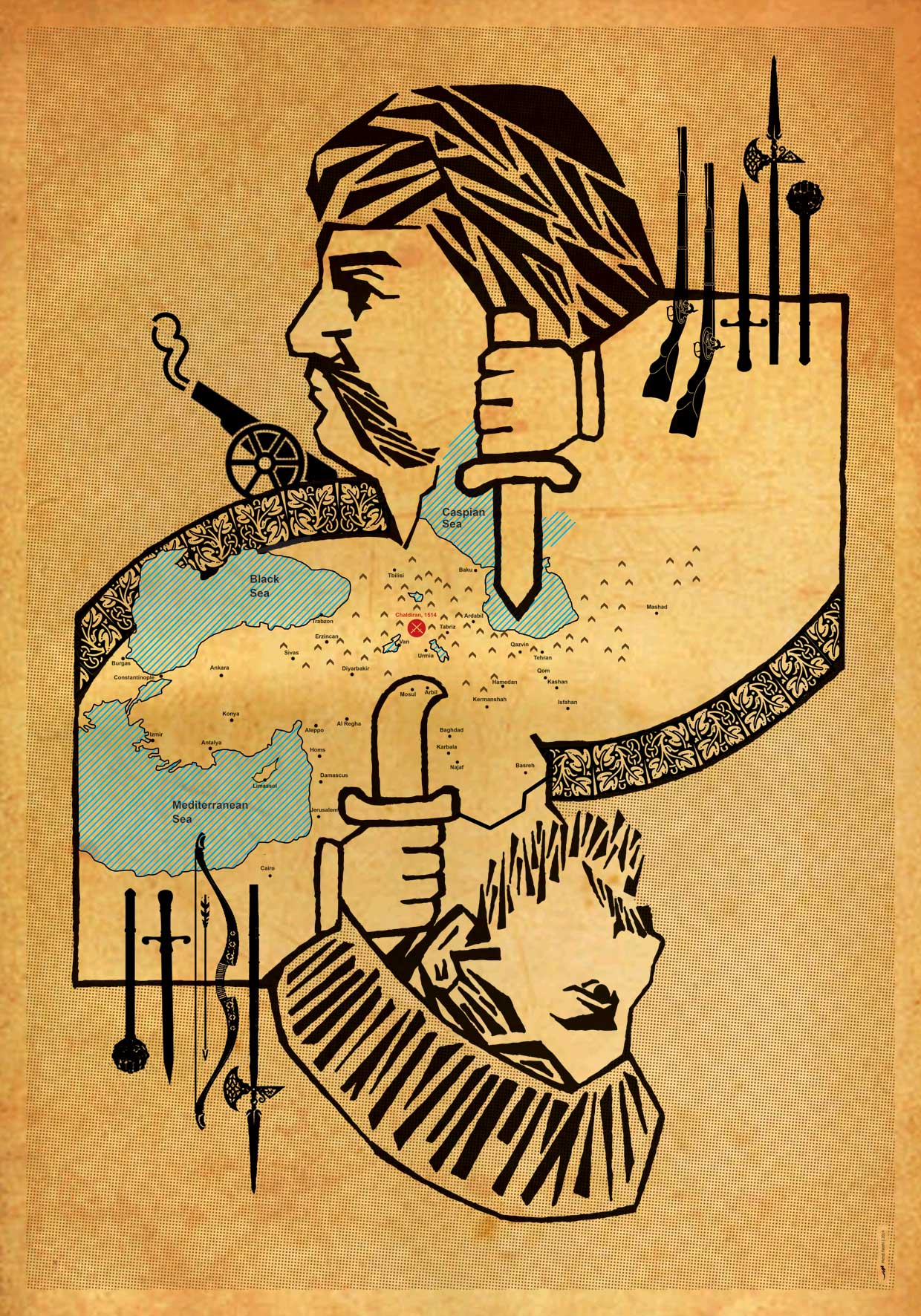

Given my ongoing fascination with the 500th anniversary of the conquest of Istanbul, I am excited to publish a guest post today from my friend Gennady Kurin about the commemoration (and non-commemoration) of the 500th anniversary of the Battle of Chaldiran in Iran. Gennady is currently a doctoral student at Cambridge researching Ottoman-Safavid relations. This cool Chaldiran graphic, designed by Mehdi Fatehi, can be seen at full size here.

The Five hundredth anniversary of the

Battle of Çaldıran and how the Ottoman-Safavid conflict has shaped the Middle

East.

The Middle East is rapidly changing. Yet, many crises the region is

currently facing and the realities it lives with remain largely misunderstood. Here

is an attempt at shedding some light on the past and the present of Turkey,

Iran and everything in between as well as contextualizing some key factors

determining the policies of these states, and showing how the shared history is

used in constructing counterproductive political discourses.

Five hundred years ago on the 23rd

of August, on a plain in northwestern Iran, today merely sixty kilometers from

the Turkish border, a battle was fought inaugurating more than a century-long

conflict between the Ottoman Empire and its eastern neighbor – the Safavid

state. The immediate consequences of this battle and the many wars that

followed were not just changes in the political landscape and redrawing of

state borders. The religious and ideological dimensions of this clash have

reshaped the Middle East, laid the foundations of some contemporary conflicts

and can be said to have created Turkey and Iran as we know them today. Thus,

anybody interested in the history and politics of this region can and should

understand it in the context of the Ottoman-Safavid struggle.

While the world is passively watching the

developments in Iraq and Syria and the Western countries are trying to decide

what their policy towards the Islamic State should be, it is in fact Turkey and Iran that are key to finding long-term solutions to some of the problems the region is now facing. Having a history of military and religious-ideological

struggle these two countries, willingly or not, seem to be slipping into

another potentially very dangerous conflict with their support for either Sunni

or Shi’a factions. And just like the ultimate outcome of this early modern

sectarian conflict the current crisis is very unlikely to bring about anything

other than chaos and destruction. This text should serve as an introduction to a series of articles about

the conflict and how it has reshaped the region in question.

Historical background:

The scene of this struggle was the region between modern Turkey and Iran,

including the Tigris-Euphrates valley and the southern Caucasus. Historically

within the Iranian cultural and political sphere of influence, the post-Mongol

period saw this region ruled by a number of Turkoman dynasties, the most

prominent of which - and in many ways the predecessors of the Safavids - were the

Qara Qoyunlu and Aq Qoyunlu[1].

The Mongol conquest of the Middle East and the destruction of the

Abbasid Caliphate in Baghdad triggered a mushrooming of various Islamic

mystical orders as well as number of messianic movements. We can hardly speak

of orthodoxy, either Sunni or Shi’a, as being strictly imposed or practiced in

the Turco-Iranian world prior to the conflict in question. Indeed, without any

central authority which at least nominally the Caliphate used to provide, a

state of religious flux might be the most appropriate way to characterize this

period of the region’s history.

By the end of the fifteenth century, the Ottomans had already become

what these days political analysts would call a super power. Having recovered

from a crushing defeat inflicted by Tamerlane in the Battle of Ankara (1402)

and the resultant civil war, they conquered Constantinople in 1453 and for a

moment there seemed to be no rival capable of challenging their dominance. This

challenge would eventually come from within their own domains - the Turkomans

of Eastern Asia Minor.

These tribes, essentially remaining outside of the Ottoman state

structure and gradually starting to feel resentment at the increasing

centralization and confessionalization of the empire, would prove to be a major

test for the Ottomans. Being associated with various heterodox (often messianic

and Shi’a-leaning) Sufi movements, they were not particularly keen on this

centralized state encroachment. And even though we do not have the luxury of

going into much detail here, it needs to be said that it was the descendants of

a Sufi shaykh - Safi al-Din of Ardabil (d.1334) - Junayd and Haydar Safavi who

succeeded in uniting those tribes and utilizing their religious enthusiasm to

achieve their political goals over the course of the fifteenth century. Both

were killed in Caucasian campaigns, however, and so it was Haydar’s son Isma’il who would complete the transformation of

the Safavi Sufi order into one of the most significant and long-reigning

dynasties in Iran’s history. Indeed, the beginning of the Safavid era also

marks the beginning of modern Iran.

Before and after the battle:

Isma’il was only thirteen (1501) when he began his career of conquest,

but within a decade he had succeeded in bringing much of Iran and parts of

Eastern Anatolia under his sway. One of his first policies was to kick-start

the conversion of the country, at the time majority of the population of Iran

are believed to have practiced various forms of Sunni Islam, to Twelver Shi’ism.

To this end, he invited a group of Shi’a clerics from what is now Southern

Lebanon to the Safavid realm. So for those who ever wondered why the Islamic

Republic of Iran, in itself a product of Shah Isma’il’s conversion policy, has

such close ties with the Lebanese Hezbullah and the country’s Shi’a community,

the answer is rather straightforward; those people are the descendants of the clerics

who over the course of the sixteenth century worked hard to spread the Shi’a

form of Islam in Iran.

The Qizilbash[2], the

above-mentioned Turkomans of Anatolia and Azerbaijan, were instrumental in

Isma’il’s rise to power and his successful campaigns. With their messianic

ideology and almost fanatical allegiance to Isma’il they would form the

backbone of the Safavid state and army. But as most of the Qizilbash came from

Eastern Anatolia, a significant part of which was Ottoman territory, they posed

a real threat to the Empire’s standing. It was not long after Shah Isma’il’s

rise to power that a number of Qizilbash rebellions, only some of which were

instigated by the Safavids, took place throughout Anatolia, culminating in the

first clash between the two states on 23 August 1514.

In the years leading up to the battle, the Ottomans were not only facing

the Safavid-Qizilbash challenge in the East, but also as Sultan Beyazıt II got

older a bloody struggle for the throne began. The least likely successor of

Beyazıt, Yavuz[3]

Selim – then a prince and governor of a province on the fringe of the Empire (Trabzon)

– would emerge victorious. Thanks to his energy and ambition Selim was

successful in securing the support of the Janissaries and organizing a

victorious Eastern campaign. His march from Edirne via Constantinople to

Azerbaijan took about five months and along the way he did everything to make

sure that his army would not get attacked on two fronts. What this meant was

‘neutralizing’ or deporting thousands of his Qizilbash subjects to as far away

as Bulgaria and Greece where their descendants are still found today.

Another move as part of Selim’s

preparations for the battle was to ensure the support of the Kurds. Inhabiting

a significant part of the lands in between the two enemies, their support would

prove instrumental in not only securing victory in the battle, but also retaining

the conquered lands. A man called Idris-i Bitlisi, an Ottoman bureaucrat and a

Kurd himself, was a mastermind behind this successful policy. He conducted much

of the negotiations with the leaders of various Sunni Kurdish factions,

rallying them against the ‘heretical’ Qizilbash and Shi’a Safavids and ensuring

their gravitation into the Ottomans’ sphere of influence. In recent years there

have been attempts to rename a famous hill bearing the name of French

orientalist and traveler Pier Loti, in the Istanbul district of Eyüp, the

Idris-i Bitlisi Hill[4].

Idris’ grave is in Eyüp, but the timing suggests more calculated motivations as

well. In an attempt to solve the Kurdish question, the Justice and Development

Party has been working hard to construct a ‘neo-Ottoman’ or perhaps even

‘pan-Islamic’ discourse into which the Kurds of Turkey would fit ‘perfectly’. Indeed,

what could be more appealing to the Kurdish electorate, at the very least that

of Bitlis, than one of the major tourist spots in Istanbul bearing the name of

their hemşehri[5]?

The two armies finally met in late summer 1514 on steppe in Western

Azerbaijan. The Safavids were not only at a numerical but also at a

technological disadvantage. The Ottoman army, 100,000 soldiers strong and

supported by artillery, faced 40,000 Safavid cengâverân [6] Qizilbash cavalry. There have been many speculations as to why the

Safavids did not use artillery, ranging from claims that they considered

firearms un-Islamic or unmanly to speculations that such technology simply was

not available in Iran at the time. According to one of the most renowned

scholars of Iranian history, the firearms were not only available in the

country decades before the battle but were in fact used by Shah Isma’il’s

father Haydar in fort sieges as well as by the Aq Qoyunlu[7].

His conclusion is that the Safavids did not use firearms at Çaldıran because they chose not to[8],

whatever the real reason behind such unpragmatic decision might have been. The result of the battle was somewhat

predictable as is the fact that this historical event is remembered differently

throughout the region.

For Turkey it was a victory, signifying the annexation of the province of

Diyarbakır and, at least in the short term, keeping the Safavid threat at a

distance. Following the battle Selim proceeded to occupy the Safavids’ capital

Tabriz but decided not to spend the winter there and withdrew to Amasya instead.

No peace treaty was signed and Isma’il took the city back within weeks of

Selim’s withdrawal. Over the next two centuries, the Ottomans would have a few

more attempts at conquering the lands of Western Iran, but would never succeed

in holding onto them for any substantial period of time. The peace treaty of

Amasya (1555), ending the second war between the two countries, would seal the

Turkey-Iran border more or less in its current place. Within two years of the

victory at Çaldıran, the Ottomans defeated the Mamluk Sultans of Egypt and took

over the title of the Sunni Caliph. Selim became the first Ottoman Caliph and

it was only during the radical period of reforms implemented by Mustafa Kemal

Atatürk in the 1920s that the Caliphate would eventually be abolished. It was a

move that naturally made many people uneasy, and many others call for its

restoration today. Currently there seems

to be an abundance of potential ‘Caliphs’, from Saudi Arabia to Iraq to Turkey,

with everybody promoting the ‘right’ form of Islam.

For the Safavids the defeat at

Çaldıran meant the permanent loss of the territory which for centuries had been

within the Iranian sphere of influence. It also meant that the Qizilbash of

Anatolia and Iran found themselves within two warring countries, with former

becoming a marginalized religious minority and the latter being largely

converted to Shi’ism and thus gradually losing their ties with Anatolia. Put

differently, one of the consequences of Çaldıran was the gradual

crystallization of a Shi’a Azeri identity as opposed to the Sunni Turkish one.

The continuous Ottoman invasions of the Safavid lands, and the repeated

occupations and sackings of Tabriz, would eventually push the Safavids to move

their capital out of Azerbaijan and away from Anatolia - first to Qazvin and

later to Esfahan. Thus, what began as a Turkish dynasty and a state by the

seventeenth century had come to assume a more Persian character, in many ways

in direct opposition to its adversaries. Shi’a Iran would become a buffer

between Sunni Turkey and Central Asia, contributing to the latter’s isolation

and relative decline. That in turn would pave the way for the annexation by the

Russian Empire in the nineteenth century.

For the Kurds, who are these days moving ever closer to attaining

political independence, albeit for now within a relatively small region of

Northern Iraq, Çaldıran and its aftermath also brought significant changes. In

his 2014 New Year message to the people of Kurdistan, Massoud Barzani made a

reference to the battle stating that it split Kurdistan[9]

and calling for Kurdish unity. Barzani is right in the sense that different

Kurdish factions ended up within two warring states. Yet considering the

linguistic and religious diversity of what the Kurds themselves would these

days refer to as Kurdistan, as well as the continuously shifting alliances

within the Ottoman-Kurdish-Safavid triangle, one can hardly speak of the

existence of Kurdish unity at time of Çaldıran. The existence of a number of

parallel discourses on this subject in Turkey and outside only seems to confirm

this.

Where the Bosphorus Strait becomes the Black Sea, today a bridge bearing

the name of Sultan Selim is being constructed. Despite being highly

controversial and having faced much opposition from various environmental and

political groups the construction is going ahead. It is noteworthy, yet

unsurprising, that millions of Alevis, the descendants of the Anatolian

Qizilbash, do not feel particularly excited about the name choice. It is also ironic

that a structure intended to connect two continents has already brought about

so much tension and resentment, not to mention the somewhat unambiguous message

from the less and less secular Turkey to a religious minority of many millions.

For Recep Erdoğan, recently elected president of Turkey, once upon a

time his current position must have also seemed very distant. Having a modest

background and coincidently also being from the Black Sea region of the country,

he has, just like Selim, gone a very long way to get to the top and I would even

dare to suggest that he is very aware of many similarities between himself and his

historical predecessor. They may well have called the bridge Recep Tayyip

Erdoğan Köprüsü, but perhaps the third Istanbul airport might be good enough

for now[10].

All these are by no means to suggest that Erdoğan is soon to face ‘Shah

Isma’il’ on the ‘battlefield’. For the current Iranian establishment Isma’il

hardly represents the right kind of piety, and is very unlikely to be a role

model for politicians and other public figures of the country.

Originally I wanted the day of the publication of this article to

coincide with the anniversary of the event but very soon I came to realize that

the actual date hardly had any resonance with any party. Today, a small

memorial and a statue of Shah Isma’il’s minister and field commander stand

where the battle was once fought, a tribute to thousands of Iranians killed in

this war. On the 3rd of May 2014 a small commemoration ceremony,

organized by the mayor of Çaldıran’s office, took place. In Persian there is a

verb meaning ‘to dust, to clean’ only used specifically for dusting and

cleaning objects of religious significance. Along with this sacred dusting and

prayer readings, then-mayor of Çaldıran, Mr Qulipour gave a short speech during

the ceremony. He made a somewhat ambiguous comparison between the martyrdom of

Imam Husain and these Safavid soldiers ‘who sacrificed their lives for Islam’

in the ‘bloodiest conflict in Iran’s history’[11].

We can only wonder how an event of such scale and significance, bearing in mind

Mr Qulipour’s choice of words and references, was not only commemorated four

months ahead of the actual date but also remain largely unheard of or even

ignored by most.

Despite the loss of the battle

the Safavids managed to preserve their sovereignty, survive for more than

two centuries and, most importantly, to make Iran the only Shi’a Muslim state in the world. The latter almost by definition implied Iran’s playing an active role in the Shi’a affairs abroad and a completely new historical trajectory. During my visit to Çaldıran on the day of the annivsary I had a chance to speak to some locals and enquire wether they knew what day it was. The answer I got was ‘Saturday’. The day before, however, saw a big commemoration ceremony of a martyrdom of another Shi’a holy figure with loud sermons and religious songs heard in every corner of town. The real lessons of Çaldıran and the subsequent wars should be the emphasis on the destructive consequences of this conflict and the dangers of repeating the mistakes of the distant past. Instead, the Islamic Republic of Iran establishment appears to be keener on framing everything in Shi’a religious terms and at least with this particular event, consciously or not, failing to point out the meaningless nature of this sort of religious conflicts either in the past or the present.

two centuries and, most importantly, to make Iran the only Shi’a Muslim state in the world. The latter almost by definition implied Iran’s playing an active role in the Shi’a affairs abroad and a completely new historical trajectory. During my visit to Çaldıran on the day of the annivsary I had a chance to speak to some locals and enquire wether they knew what day it was. The answer I got was ‘Saturday’. The day before, however, saw a big commemoration ceremony of a martyrdom of another Shi’a holy figure with loud sermons and religious songs heard in every corner of town. The real lessons of Çaldıran and the subsequent wars should be the emphasis on the destructive consequences of this conflict and the dangers of repeating the mistakes of the distant past. Instead, the Islamic Republic of Iran establishment appears to be keener on framing everything in Shi’a religious terms and at least with this particular event, consciously or not, failing to point out the meaningless nature of this sort of religious conflicts either in the past or the present.

There is one more parallel to be drawn between AKP Turkey and the

Islamic Republic of Iran and their historical doubles. It is the role both

countries have been trying to play in Syria and lately in Iraq. With Turkey at

least indirectly backing the Sunni and Iran the Shi’a (or the Syrian Alawites,

not to be confused with the Alevis of Turkey or Iran) factions we can hardly

say that the region is entering an era of peace and prosperity. In one of his

recent public statements Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani made it very clear

Iran would intervene militarily should the Shi’a holy cities of Najaf and

Karbala be threatened by the Islamic State militants. We can only speculate as

how the more radical factions within the Sunni world would feel about Islamic

Republic’s direct intervention in the Iraq crisis[12].

One thing we can say with degree of confidence is that there will be no

shortage of comparisons between the IRI and the Safavids.

History can be a powerful tool at the disposal of modern states for good

and bad. Unfortunately, it too often seems much more convenient to make an

easy-to-relate-to comparison with some Shi’a holy figure’s martyrdom, a hemşehri or a sultan. Yet where there exists an opportunity to

learn from the mistakes of the past as well as those of the others it is very

unfortunate to see different people ‘stepping onto the same garden rake’[13]

again and again.

In addition to the references below, anyone interested in finding out more about this subject can consult either of the works below or watch a discussion of Chaldiran at Manchester University with Colin Imber and others from October 23, 2014: https://www.youtube.com/watch?

In addition to the references below, anyone interested in finding out more about this subject can consult either of the works below or watch a discussion of Chaldiran at Manchester University with Colin Imber and others from October 23, 2014: https://www.youtube.com/watch?

İranlı Tarihçilerin Kaleminden Çaldıran (1514), by Vural Genç; (2011, Bengi Yayınları, İstanbul)

Shah Isma'il va Jang-e Chaldoran, by Hashim Hejazifer with an introduction by Muhammad Isma'il Rezvani;(1995, Publication of Iran National Archives Organization, Tehran)

[1] Black and White Sheep,

these two dynasties ruled much of Eastern Asia Minor, Iraq, and Western Iran at

various times during the 14-15th centuries.

[2] Red-heads, called so for their characteristic red headgear.

[3] Yavuz in Turkish means grim, a much deserved nickname.

[4] http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/gundem/20952795.asp

[5] Fellow townsman.

[6] Those who go to war, warriors, heroes.

[8] İbid.

[9] http://krp.org/english/articledisplay.aspx?id=euDLHFUUFTw=

[10] http://www.radikal.com.tr/turkiye/ucuncu_havalimaninin_adi_recep_tayyip_erdogan_havalimani_olacak-1206623

[11] http://chaldoran.mihanblog.com/post/886

[12] http://en.trend.az/azerbaijan/politics/2305588.html

[13] A Russian proverb.