For a full sized image click here

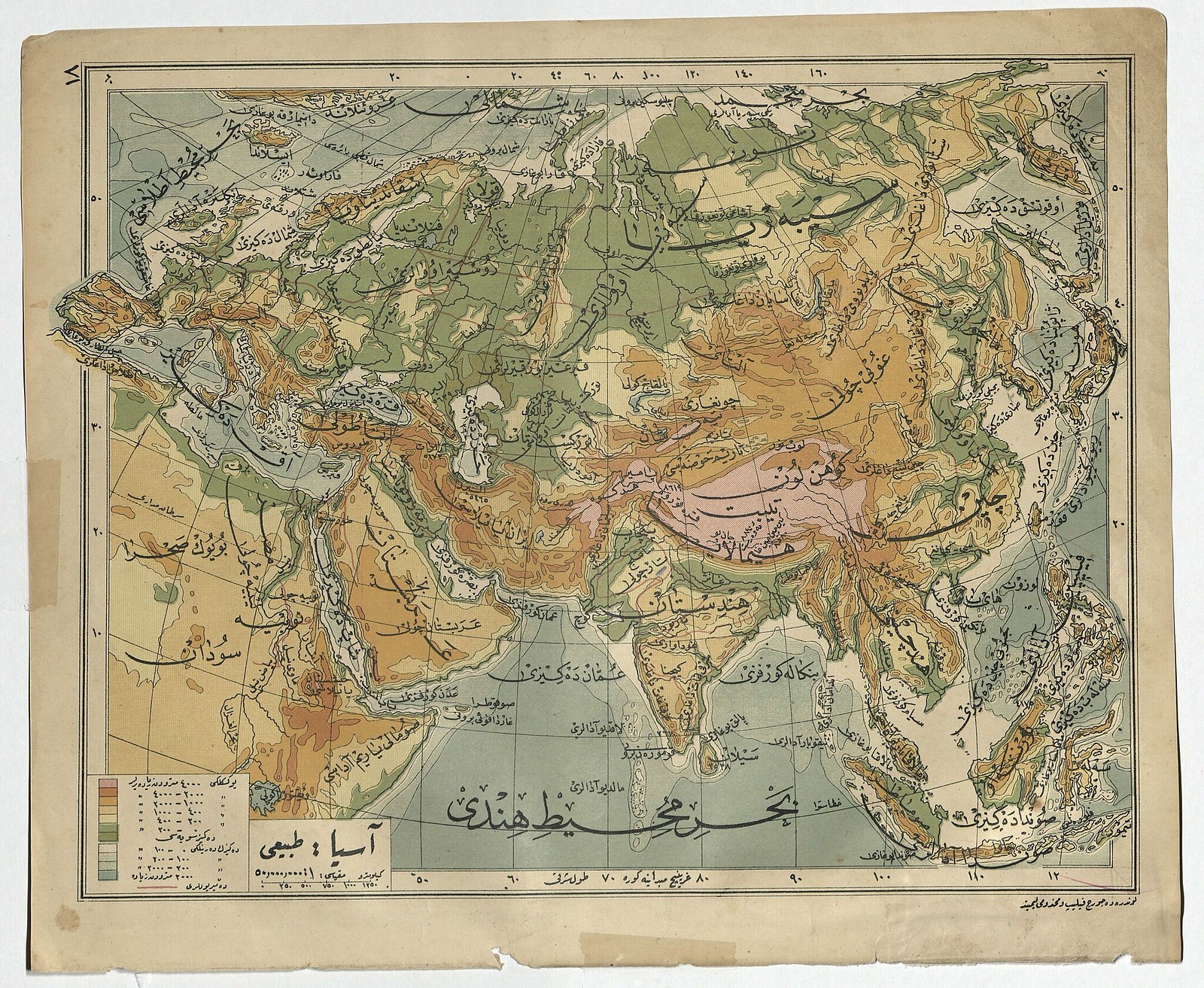

For a full sized image click hereToday, three maps of Asia. First, a late Ottoman physical map of the continent made by George Philip and Sons. Not much to say besides this might be one of the nicest looking maps ever made. I mean check out the close up to the left, or the shade of pink used for Tibet. It's impressive too that in spots like Siberia the map's makers have managed to have place names intersect without any loss of legibility.

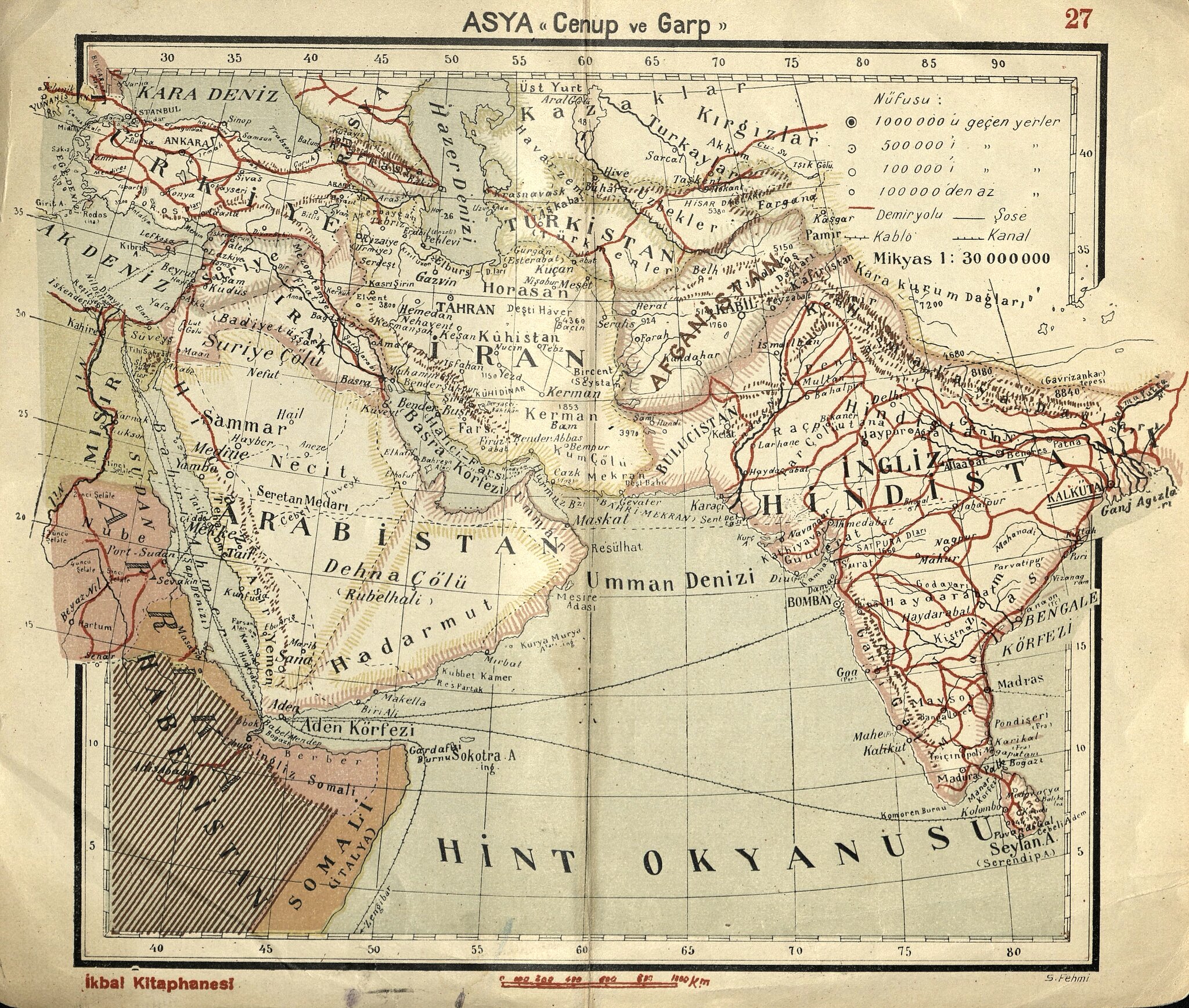

Second, a map of southwest Asia from an inter-war atlas bringing together some themes from earlier maps: Turkey's train network (almost on par with India's), the Hijaz Railway, Iran's complete lack of trains (an impediment to transporting opium), and the Soviet national delimitation in Central Asia (here the mapmakers seem to have included the new nations as ethnic groups and kept the old Czarist political label of Turkistan). There's something strange going on with the Turkish Iraqi border too, that will hopefully be the subject of a future post. Though at this point in time Istanbul's printing houses clearly didn't have the ability to achieve quite the same visual elegance as British printers, relatively cheap maps like this managed to reach wider audiences and offer a perspective on the wider world to a new, increasingly literate generation.

And finally, a very early Republican map of Asia with some analysis by Chris Gratien.

|

Late Ottoman Map of Asia: for a full size version click here.

"This map

of Asia, from the education ministry's miscellaneous papers, shows the

way the Ottoman interest in Asian geography may have become problematic

for the new Republican Government. An inscription at the bottom says

this map was available for sale in Fatih on Kasaplar Street in İranlı

Mehmed Ağa's shop across from the police station. While the map bears no

date, it was found in two copies within a folder labeled circa 1339

(1920/1921) and in a box full of documents issued by the Grand National

Assembly of Turkey during this period of transition. Turkey was

not officially recognized as a sovereign state until 1923, but by 1920

the Ankara-based government was already removing Ottoman institutions

and symbols to create a new government.

"The map is a geographic one more than political, although some political boundaries are traced, rather befitting of a time in which the boundaries of empires and nations were shifting. The borders of Asia itself conform to the conventional European definitions of the time: the Caucasus and the Urals, so most of Russia is labeled as Europe and therefore receives no detail. In fact, no reference to the Russian state appears in Asia on this map. The Ottoman domains are labeled as Ottoman Asia (Asya-yı Osmani). While administratively the Empire was not divided this way, it conforms to the way Europeans conventionally divided the empire with concepts such as Turquie d'Asie. This geographic issue may have been less of a problem when the Ottoman state was still an empire with territories in Europe seeking to be part of the European state system, but the question of Asia's limits might have given more pause in republican Turkey given that only a very small piece of the nation-state remained in conventionally defined Europe."

"The map is a geographic one more than political, although some political boundaries are traced, rather befitting of a time in which the boundaries of empires and nations were shifting. The borders of Asia itself conform to the conventional European definitions of the time: the Caucasus and the Urals, so most of Russia is labeled as Europe and therefore receives no detail. In fact, no reference to the Russian state appears in Asia on this map. The Ottoman domains are labeled as Ottoman Asia (Asya-yı Osmani). While administratively the Empire was not divided this way, it conforms to the way Europeans conventionally divided the empire with concepts such as Turquie d'Asie. This geographic issue may have been less of a problem when the Ottoman state was still an empire with territories in Europe seeking to be part of the European state system, but the question of Asia's limits might have given more pause in republican Turkey given that only a very small piece of the nation-state remained in conventionally defined Europe."

BOA, MF-VRK 50/39 (1339)